A short plane ride from here, a city once crushed beneath the weight of skyrocketing rents and eye-watering property prices has found a solution to the type of housing crisis plaguing Australia’s major cities.

While bold and quite controversial, the fix was relatively simple, quickly implemented and highly effective, dramatically boosting housing supply in a short period of time.

As a result, rental prices came down and runaway home price growth stabilised.

It’s the kind of scenario millions of Aussies would warmly welcome, given the dire state of housing across much of the country.

“When it comes to housing policy outcomes, this is a compelling experiment that could certainly go a long way to addressing some of our issues,” economist Matthew Maltman told news.com.au.

Our worsening housing crisis

Whether renting or buying a home, PropTrack economist Angus Moore said the past few years has been “incredibly tough” for many.

“If you’re looking to buy a home, housing affordability is currently at its worst level in at least three decades,” Mr Moore said.

“If you’re a renter, prices nationally have risen by 10 per cent in the past year. The rental vacancy rate, that is how many homes are on the market to lease, is just 1.1 per cent. That’s extremely low.”

At the same time, home prices have defied almost all expectations and continue to grow, up 3.5 per cent nationally over 2023.

That’s despite a rapid four per cent increase in interest rates since May 2022, which was expected to put downward pressure on markets but didn’t.

A combination of factors got us here, but one of the biggest contributors is housing supply, Mr Moore said.

When it comes to supply, Australia has among the lowest levels of housing per person of any country in the OECD – about 400 homes per 1000 people.

Successive failures of governments at all levels have only made the problem of supply worse, with support measures like grants and concessions only serving to boost demand from buyers.

The fix across the ditch

Back in 2016, frustrated officials in Auckland came up with a bold and sweeping solution to the city’s crippling housing crunch.

It instantaneously ‘upzoned’ three-quarters of residential land in New Zealand’s biggest city, effectively removing restrictions on higher-density development.

“The policy itself is interesting,” Mr Maltman said.

“In some areas, like those around transit settings in the inner-city, they’ve allowed quite high density development, but generally, for most of Auckland, it’s a principle known as ‘three-by-three’ – three dwellings, no more than three storeys.

“The number of multi-unit building consents spiked very quickly when the policy was introduced. Then, as market conditions improved in the years after, they accelerated even more.”

Inefficient single home blocks were converted into multi-dwelling sites right across Auckland.

In-depth analysis by Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy and Peter Phillips from the University of Auckland concluded that 21,808 additional dwellings were built in the five years after the upzoning reforms – equating to four per cent of the city’s total housing stock.

“That’s a large number,” Mr Maltman said.

Dr Greenaway-McGrevy also conducted research on the impact of that boosted supply on rental prices in the city, which he estimated were 12 to 25 per cent lower than they otherwise would’ve been.

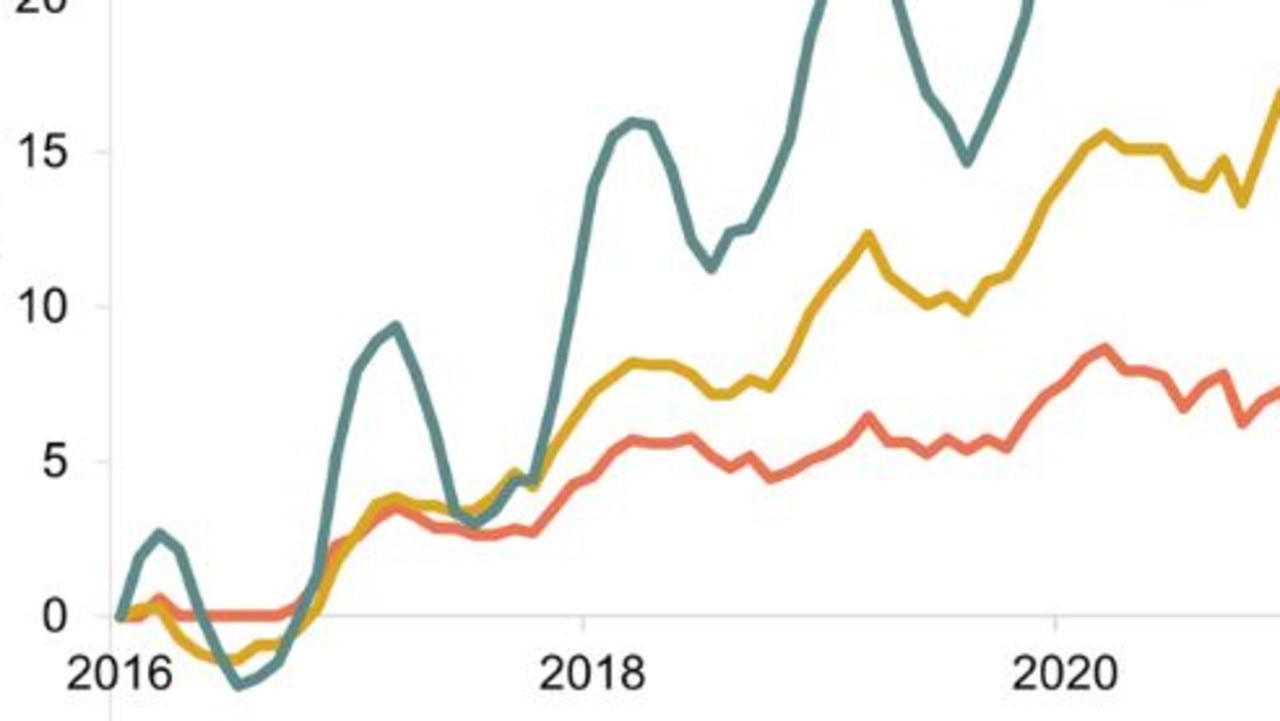

Before 2016, rents in Auckland were skyrocketing. A few years later, as new homes started to be completed, prices plateaued.

“It’s at this point Auckland diverged from the rest of the country,” Mr Maltman said.

“In real terms, rents about the same as they were in 2016, but in the rest of the country, rents are 10 to 15 per cent higher in real terms.”

Home prices also stabilised over the same period, growing at a slower pace than in other cities in New Zealand, he said.

“The market has also been more stable to price shocks like interest rate changes.”

Australia should copy the plan

Inaction on the issue of supply has destined countless Aussies to grapple with precarious housing futures, with high prices locking out younger would-be buyers and keeping them in a rental for longer, if not forever.

The surging cost of rent is pushing more people into ‘housing stress’ – a scenario where the cost of leasing a property is more than 30 per cent of one’s income.

That’s if they can even find a home in the first place, with sights of long queues of people at open homes on any given Saturday becoming commonplace.

At a meeting of the National Cabinet in August, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and state and territory leaders agreed on details of the so-called National Planning Reform Blueprint.

In it, the existing target of building one million homes over the next five years was boosted by an additional 200,000 dwellings.

Grattan Institute modelling suggests those 200,000 extra homes, when built, could reduce rents from where they might’ve been by about four per cent. That equates to a savings of $8 billion for renters over the first five years, the think-tank said.

“If those higher rate of construction are sustained for a decade, rents could fall by eight per cent, saving renters $32 billion total,” it said in a submission to a parliamentary inquiry earlier this month.

“But these gains will only be realised if state and territory governments undertake necessary reforms to land use planning rules to allow more housing to be built.”

That’s where the major hurdle is – figuring out how to actually build those homes, Mr Maltman said.

“It’s very nice to talk about supply and the government wanting to help, but at some point we’ll need concrete solutions. I think this example, from a city not far from us and in a comparable situation, should be at the top of the list.

“It’s one we could adopt pretty easily here in many parts of the country.”

Mr Moore agreed and said the Auckland experiment showed boosting supply works to ease rental price pressures.

“It’s far from the only example. Minneapolis in the US did something pretty similar in liberalising restrictions on what’s terms as the ‘missing middle’ – two- to three-storey, semi-detached, multi-unit dwellings in places that would previously only allow single-dwelling homes.

“What that kind of change does is allow an enormous increase in building activity, boosting the supply of homes, and the impact of that is lower rents.

“It’s a model we should be looking at given the evidence suggesting it’s extremely effective in boosting supply and putting downward pressure on rents.

“Given where our rental markets are at, it’s an idea worth exploring.”

What’s being done now?

Housing affordability is a key area of focus for the government and the passage of the $100 billion Housing Australia Future Fund has been heralded as a reason for optimism.

But a number of advocacy groups say the HAFF does not go far enough, with the Australian Council of Social Services urging Mr Albanese to see it as “a floor” on which to build up.

“It is not the whole solution and more needs to be done to make meaningful inroads on the housing crisis,” ACOSS boss Cassandra Goldie said.

“ACOSS continues to call on the government to invest directly in constructing 25,000 social and affordable homes per year for 10 years.

The Grattan Institute report concurs that “housing inequality won’t really fall until more housing is built”.

But on top of increasing supply, the Grattan Institute called for a range of measures to be considered, from slashing the capital gains tax discount offered to investors and winding back negative gearing benefits.

It concedes the effect on home prices would be “modest” – about two per cent lower than they otherwise might be – but the impact on homeownership rates would be “a lot larger” because first-home buyers could have a chance to outbid investors.

In the short-term, the Grattan Institute has called for immediate measures to support those most in need via an increase to welfare payments.

The Commonwealth Rent Assistance payment is meant to help ease the burden of high housing costs, but research by UNSW found 37 per cent of recipients are currently living in poverty.

Simply put, the amount on offer – a median of $69 per week – is wholly inadequate compared to average rents, which have skyrocketed in recent years, researchers concluded.

The benefit of sufficient welfare was demonstrated during Covid when the government rolled out boosted and new emergency assistance payments. In the first three months of the pandemic, the rate of poverty plunged by 5.7 per cent – or 383,000 people.

“Covid income supports – especially [the] Coronavirus Supplement – likely contributed substantially to this outcome,” the report noted.

“Another factor contributing to reductions in poverty at this time was the rent ‘freezes’ imposed by state and territory governments to ease financial hardship during Covid lockdowns.”

The near future in New Zealand

The success of the Auckland model prompted the New Zealand Government to adopt a nationwide approach, dubbed the Medium Density Residential Standards, passing legislation requiring urban councils to allow a wider variety of homes to be built.

“New Zealand has a shortage of affordable housing [and] a key driver of this shortage is restrictive planning rules, which limit the heights and density of housing in residential areas,” NZ’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Development said.

“The Act [removes] these restrictive rules, so we can expect to see more medium density homes being built across more of our major cities. This will mean more homes are built in areas that have access to jobs, public transport and other public amenities and community facilities.”

Analysis by PwC indicated the policy could deliver up to 105,000 new dwellings over five years – no small feat in a place with a population of five million.

But as the country heads to an election, that legislation hangs in the balance. National, the Opposition party, had initially provided Labour bipartisan support for the measures but has now withdrawn it.