A stark summary of what life is like for young adults in Australia these days amidst the high cost of living, housing crisis and economic inequality has gone viral.

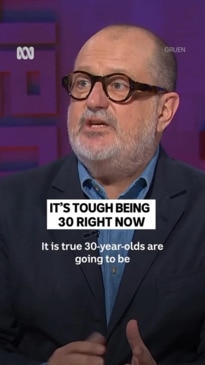

A scathing and accurate assessment of the ‘extremely difficult’ situation facing millennials from Russell Howcroft, advertising guru and panelist on the hit ABC series Gruenpainted a bleak picture.

“It’s the hardest it’s ever been … in history for a 30-year-old in Australia,” Mr Howcroft said on the show last week.

“It’s true that 30-year-olds will be less well-off than their parents.” It’s a fact.”

A big driver of the generation gap is the rapid rise in home prices, which have risen more than 380 percent nationally since 1992.

Mr Howcroft revealed that when he was 30, the house he bought cost about three times his annual salary.

“Now, [it’s] eight times plus for a 30-year-old,” he said.

“That’s what it’s going to cost you to get into the housing market.”

The cost of repaying HECS debt after university has also doubled over the past 15 years, leaving young people with heavy burdens well into their working lives.

“[It has] went from a $15,000 bill to a $30,000 bill,” he said.

“And it’s true that a baby boomer paid half the taxes … when they were 30 that a 30-year-old pays now.” So it’s extremely difficult.”

The footage has been shared multiple times on social media, with comments from young Australians feeling the struggle.

“Luckily my rent is going up fifty bucks a week ‘cost of living’ so my landlords who own our entire block can get through these hard times,” wrote one.

Another said: “The boomers took the ladder with them on the way up.

“So are we doing anything to fix this? Or are we still just talking about it?” one quipped.

But some did not buy Mr. Howcroft’s argument and placed the blame for the hard times squarely on the shoulders of millennials themselves.

“We Boomers didn’t have $6 takeaway coffees or 25 broken avo brekkies, we brought lunch from home and fish and chips with potato cakes was our weekend.”

Experts say that kind of simplistic counterpoint is flawed and misses the bigger picture that, by almost every measure, young Australians today are worse off than any previous generation.

Life is harder than ever

Prominent economist Danielle Wood, chair of the Productivity Commission and former chief executive of the Grattan Institute think tank, detailed the rough economic hand of young people.

Delivering the Giblin Lecture late last year, Ms Wood said the cost-of-living crisis and high inflation had added short-term strain to much longer-term systemic issues.

“Australia’s young people are coming through the cost of living crisis with less economic fat and the main policy tools to respond to the inflation thrust upon them,” she said.

“For today’s young people, the slow issues of a strained education system, unaffordable housing, the climate crisis and growing government debt loom large.”

She said that the economic and social systems in which young people find themselves have prioritized the needs of older generations – “sometimes by accident and sometimes on purpose”.

The perception that young people are frivolous with their money, favoring smashed avocado toast over financial responsibility, is wrong, Wood said.

In fact, young people spend less than older generations at that point in their lives on non-essentials, with “any growth in spending … due to essentials.”

Despite being more educated than those young people who came generations earlier, millennials don’t necessarily earn more.

Since the turn of the century, real wages have fallen for young Australians.

Economist and author Alison Pennington, who wrote the book ‘Gen F’d? As young Australians can reclaim their uncertain futures last year, they said young people were “feeling the terrible weight of a society that is failing them”.

“Existential doom and mass disempowerment are taking over the thinking of young people,” Ms Pennington wrote in an analysis for Conversation.

“They are trying to make the right choices against a backdrop of collapsing collective movements and government inaction against a strained global fossil fuel sector.”

The sense of economic excuse comes with “lifelong consequences” in terms of employment, health and general well-being, she said.

“It’s not surprising that many young people have given up.”

‘Jane Austen’s World’

Those experts who believe in a huge transfer of wealth to come when the baby boomers fall off their perch also ignore important context, Wood said.

It’s true that most of the record $14.8 trillion in household wealth is held by older Australians, meaning “there’s an awfully big pot of wealth to be transferred”.

But those who will benefit the most have already won the “birth lottery.”

“Among those who received an inheritance in the past decade, the richest 20 percent received on average three times as much as the poorest 20 percent,” she said.

“The Productivity Commission predicts that among current retirees, only 10 per cent of all bequests will account for even half the value of the bequest.

Thanks to medical advances and a higher standard of living, those lucky enough to receive a decent inheritance from mom and dad are likely to see that money later in life.

“The most common age to inherit is in the late 50s or early 60s – much later than the money needed to ease the middle-age squeeze of housing and children [Millennials] face,” said Mrs. Wood.

“Large intergenerational transfers of wealth can change the shape of society.” They mean that a person’s economic performance has more to do with who their parents are than their own talent or hard work.

“French economist Thomas Piketty has warned of a ‘Jane Austen world’ in which inequality is exacerbated by increasing inheritance.”

“Mitigating intergenerational inequality means policies that work for an entire generation, not just those lucky enough to have a private safety net.”

The rise of ‘generational rent’

Some people point to the misguided stereotype that young Australians would rather ‘live large’ than buckle down and save a deposit for a house.

But the reality is that securing a piece of the so-called Great Australian Dream has never been harder.

Until the late 1990s, house prices rose at roughly the same rate as wages, meaning that most people were able to keep up with changes in the market.

But between 1992 and 2018, property prices exploded at three times the rate of wage growth.

The impact of that widening gap is clear.

“Since the Second World War, Australia has been a nation of home owners,” Wood said.

“The homeownership rate peaked at more than 71 percent in 1966. Nearly three-quarters of the nation was on the property ladder and living the dream—home ownership was celebrated as an indicator of success, security and quality of life.

“Ownership rates declined very gradually over the following decades, but then sharply from the early 1990s, when house prices and incomes began to diverge.”

Overall, home ownership rates are now at their lowest level since the middle of the last century.

“But what’s particularly striking is the decline among young people,” Wood said.

“In 1981, when the boomer generation settled down and had families, 68 percent of 30- to 34-year-olds owned their own home.” In 2021, the equivalent figure was 49 percent.

“The declines have been particularly pronounced among poorer, younger people, challenging the suggestion that declining ownership rates reflect the different preferences of today’s young people.”

Young Australians aspire to own their own home just like previous generations, but the ability to do so is only attainable for “the wealthiest young people or those with the wealthiest parents”, she said.

As a result, the time it takes to build up a deposit has increased from about seven years in the early 90s to more than 12 years these days.

And the cost of paying off the mortgage is painfully high thanks to higher loan amounts and the Reserve Bank raising interest rates.

“The next time Uncle Boomer regales you with horror stories about the 17 percent interest rates of the early ’90s, it’s worth reminding him that six percent rates today are just as painful for the typical borrower as 17 percent back then,” Ms. Wood pointed out.

All of these factors combine to mean that the proportion of young Australians renting their home is high – and many will be in the rental market for their entire lives.

More casualties on the horizon

Things are only going to look worse for those Aussies who are hot on the heels of the millennials.

A 2022 Pew Institute survey found that an overwhelming majority of people across the country believe that children growing up today will be financially worse off than their parents.

And they seem to be aware of the dire situation they face.

Late last year, a survey of young Australians by Scape for its Gen Z Wellbeing Index found that one in three respondents struggled with their mental health and two thirds had sleep problems.

When asked what keeps them up at night, 78 percent said the cost of living was their top concern, while 67 percent were worried about housing affordability and skyrocketing rents.

Those issues ranked higher than concerns about climate change at 60 percent.

Similarly, headspace’s latest National Youth Mental Health Survey asked young people to name their top three problems.

The top three problems identified are financial instability, cost of living and housing affordability.

“When asked to describe how worried they were about being able to one day afford their home, 71 percent of participants said they were fairly or very worried, while 61 percent told headspace they were fairly or very worried about rent costs,” it found is research.

As a result, more than half of respondents aged 18 to 25 were hesitant to have children one day due to cost pressures.